A few years ago, at a Fourth of July party, a friend brought along photocopies of the Declaration of Independence for us to read aloud. There was beer involved so I might not have taken it very seriously. My friend did, though. There wasn’t an ounce of cynicism in his voice as he read a paragraph and passed the paper along. We really did take turns (between giggles) reading it aloud. Some wiseass might have been piping the Battle Hymn of the Republic through his pursed lips. Someone else might have been saluting an invisible flag. It might have been me.

We were young and dumb, but we had this vague notion that this was somehow a proper thing to do on July 4th. We wanted to acknowledge those who’d fought for our independence, and to really examine the words that launched the movement in the first place. How long had it been since any of us had actually read any of our country’s founding documents, anyway?

It’s definitely not something I would have initiated, but I was happy to go along with it. I am not a flag-waving American. I find our national history (as I find most histories of colonization) a mixed bag of horror and galling nerve. I find our world history even more mind-boggling. Reading anysort of original doctrine (I’m looking at you, “Holy Bible”) that has since been even a little bit compromised is both heartbreaking and confounding.

When our friends invited us over for Memorial Day this year, I made the requisite potluck item and settled in for a good meal and some pretty standard conversation. I thought back to that July 4th and smiled. My friends and I are older now, not given to half-assed attempts at interpreting doctrine while under the influence of booze. Friends had been posting pictures of relatives in uniform all day on Facebook. It was all very serious and mindful stuff now.

I had a grandfather who was in the war. He was born in Poland and half fought, half-fled his way to London, where he eventually married after the war and emigrated to the U.S. Till the day he died, he wore pressed slacks, black socks, and a button down shirt. In the summer, he might have slipped brown orthopedic looking sandals over those black socks. He spoke several languages. He was European through and through. He was from another place and time altogether.

In school, we were taught about the geography, the ideology, and the horror of the war. We were taught a deep and lasting respect for the dead. I watched endless PBS specials about the secret units and bomb squads. I picked up Mein Kampf when I was fifteen years old to try to understand more about the man who was behind it all. I read Hiroshima that same year and shook as I turned the pages. From grammar school on, we seemed to read a canon of literature produced exclusively by men who had returned from war and subsequently entombed their feelings in the pages of their manuscripts: Hemingway, Vonnegut, Salinger. I ate it, dreamt it, and swam in it. The war was alive all around me as a child. My greatest fear: that there would be a third World War in my lifetime. Though he never talked about it, my grandfather’s connection to the war- torn parts of Europe were always with him, and therefore always with me.

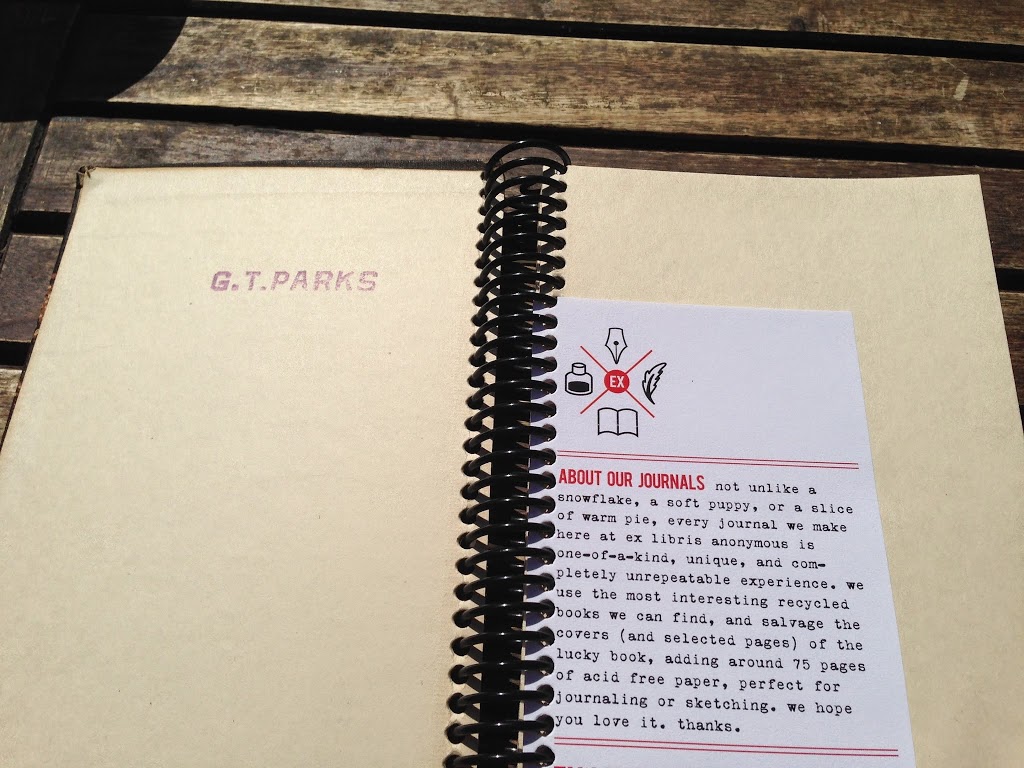

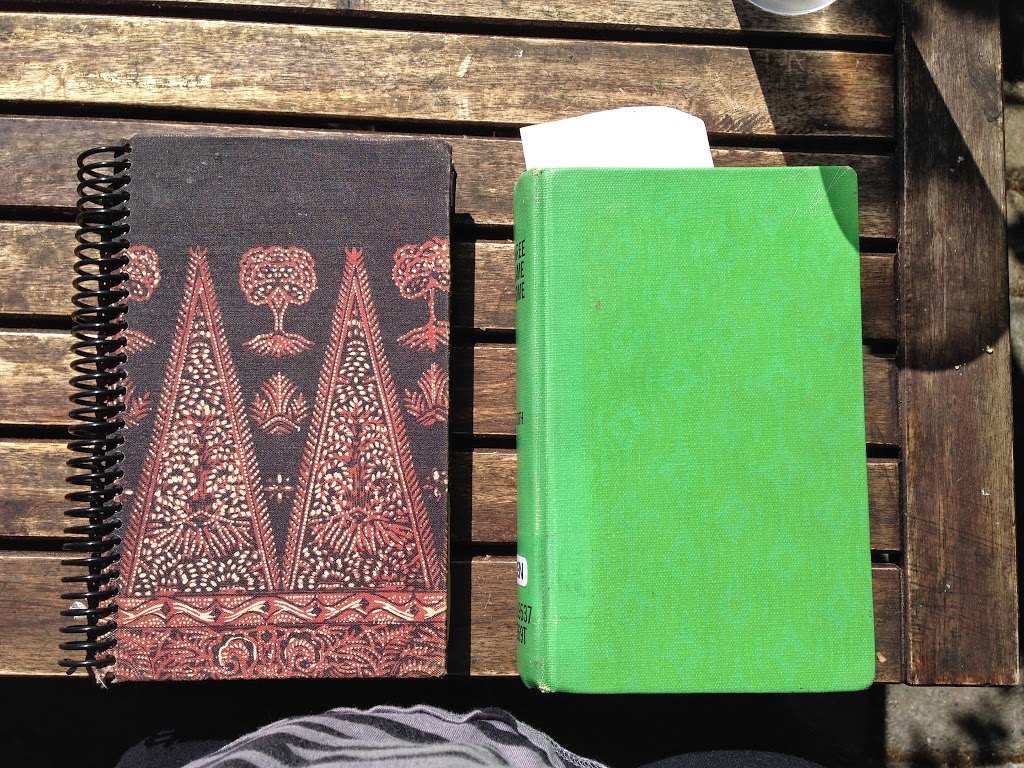

At Christmastime last year, I went to the craft fair in my neighborhood to pick up some gifts. I made my customary stop at Ex Libris Anonymous’s booth to re-up my journal stash. I’ve used Ex Libris’s journals almost exclusively for several years now. They’re based out of Portland, OR, and they take out-of-print books, chop out their innards and use their covers to bind new, acid free paper into spiral notebooks. They are lovely, and come in a variety of shapes. I always buy the smaller ones so I can travel easily with them. I picked up a few to last me till next Christmas. The one I was most excited about was small and beautiful. It had a canvas cover printed with a cool graphic that reminded me of pine trees. It smelled, deliciously, like an old book.

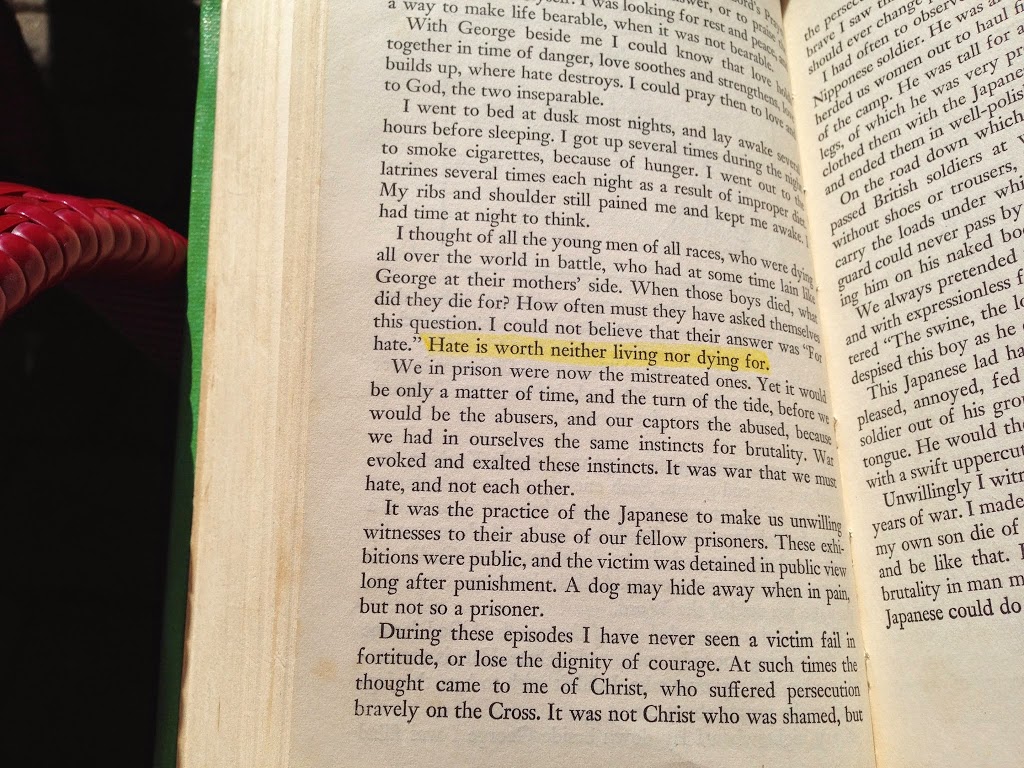

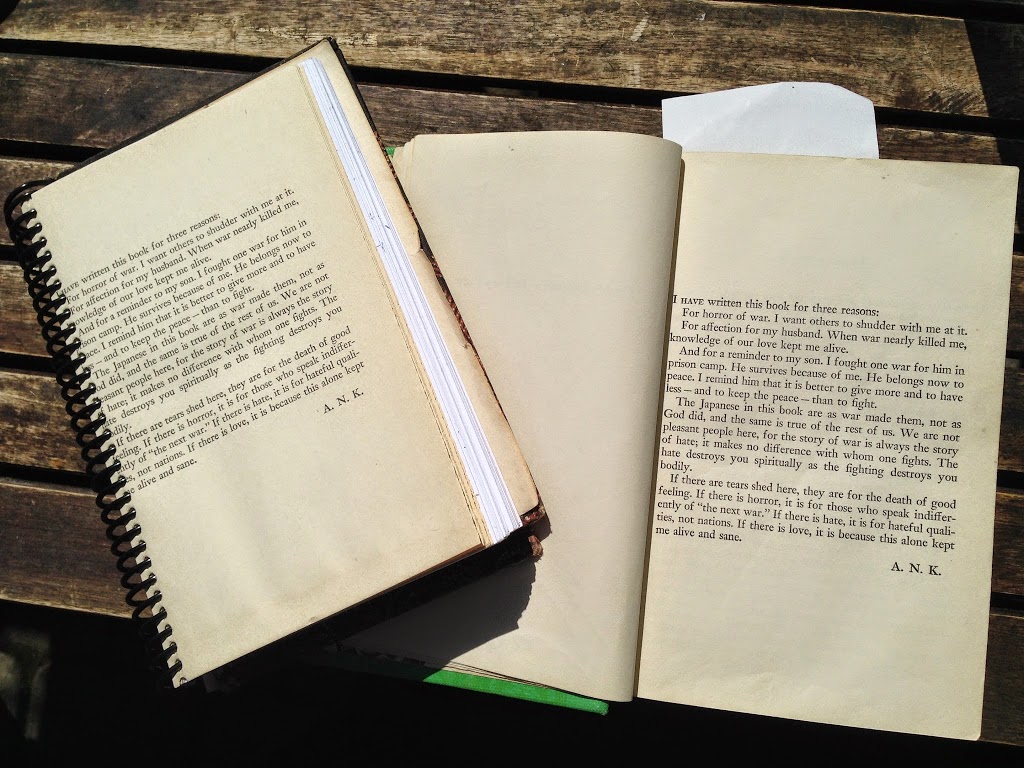

Now, Ex Libris usually tucks a few pages of the old book in with the new paper. It’s a neat feature. You’re scribbling along, you turn the page, and all of a sudden, the quality and texture of the paper changes, and now you’re looking down onto the yellowed pages of a book that’s older than you are. Trippy. Usually, I scan a few lines, and continue on with my writing. Out of context, the lines from that old book don’t really do anything for me. Plus, so much of it is either stuffy old English or technical writing, so it’s not compelling. This book, though, was different. I read ALL the pages tucked in and I couldn’t stop. I learned that, first, the book had been written by a woman. Second, I discovered the book was about the war. Those few pages were gripping, even out of context. So I did something I never do with these journals: I looked up the original book and reserved it at the library.

A week or so later, I had it in my hands: a book published in 1946 by the American journalist Agnes Newton Keith who had been rounded up in Borneo, along with her infant son and British civil servant husband, and placed in an internment camp run by the Japanese during their occupation of Malaysia. The book was Three Came Home.

Keith had to hide the notes she took during her three and a half years of internment. Had she been found out, she would have been put to death. She stuffed her notes into her son’s teddy bear, into the false bottom of a tiny wooden stool, and into tins that she buried beneath her barracks. She had three years of notes by the time she and her son and husband, all nearly dead of malnutrition and disease, were freed. Australian forces liberated the camp in 1946.

I’ve only ever read (aside from snippets of Ann Frank’s diary) one other personal account of the war from a woman’s perspective: A Woman in Berlin mysteriously showed up one day at an office I was working in at the time. It was also written by a journalist, a woman who wrote her notes on old newsprint with a pencil stub by candlelight and hid them until after the war.

I devoured Keith’s book, even though it was hard to take. I had to put it down from time to time the same way I had to put down Hiroshimawhen I was a teenager. As a journalist, Keith tried to remain as objective as she could, and she related her experience with blunt force honesty. There are some dated references to groups of people and cultures that simply would not fly in today’s world, but the overall message of the book is one of non-judgment. She makes the claim throughout the book that men are not evil; it is war that makes men evil. Even as she is nearly starved to death, beaten, and intimidated with news of brutality in the men’s camp (husbands were separated from their wives and children), she maintains the hope that each side, Japanese and American, will see each other’s humanity. She looks forward to eventual friendship between the warring nations. Her son’s survival and her fighting spirit sustain her over those three and a half gruesome years.

The things both these women had to live through are almost beyond my capacity to take them in. There are days when I feel like I have that same fighting spirit coursing through my veins. And there are others when I feel like I wouldn't have what it took to rock my sick child through the night in filthy barracks, fevered from malaria, with nothing but weak tea and boiled, inedible weeds sustaining my failing, bruised body. To read about it in a book is one thing. To live it, to shut out everything and simply grit your teeth to live another day- that is something else entirely.

During our Memorial Day dinner, a friend told us he’d just come across the letters of his grandfather to his grandmother during the war. The grandfather wrote his wife and four-year-old son every day. He included drawing with his letters. He made the war a knowable, map-able place for his child without exposing him to the terror of it. The whole story of it- his injuries, the tragedies that befell him after he came home, the way his family’s history was permanently altered- it was almost as unthinkable as Keith’s story. To have, as another friend at the table said, “his wife keep safe this piece of him while he fought”… and then to come home and lose it all… it was unreal, to say the least.

The thing that always astounds me about stories like these is the human will to keep going. There were no grand gestures in my family’s history, or anyone else’s I know, around this will, but it happened. That mandate to carry on occurs between those big moments in life, it seems. It happens in the smallest decisions: to plant a garden, to apply to school, or to stand in that line for five more minutes. Eventually all those moments add up to something much bigger, a move to America, say, or the decision to get married, or have a baby. To us, in retrospect, they look like long term plans to survive, but to the people living those lives, they were just ordinary short term choices, made during extraordinary times.

Seated at that table, I flashed through all the wars since WWII, and all the national crises we have endured as a nation, and I thought about our current generation coming up with what social critics call a sense of entitlement. I thought about the injuries the soldiers who fought in WWII sustained and the life-saving drugs unavailable to them…. and I thought: my God, no wonder thatgeneration thought every generation afterthem was a bunch of wimps. Talk about “human will”. Geez.

We clinked glasses in honor of our grandparents and I was overcome with ambiguity and gratitude because the whole of war is a muddied thing, and as a human being, I have a hard time being thankful that innocent lives were ended so that other lives were saved. After the toasts, I had this phrase stuck in my head: the endurance of the human spirit. All of us approaching our forties and beyond were sitting at this table enjoying a home-made meal, each of us comfortable and secure, because of that endurance. None of us had to worry about bombs going off in our own cities or where our next meals were coming from because of that extraordinary spirit. Soldiers or not, all my ancestors deserve my gratitude. I am here, alive and well, trying to improve the world in my own small way, because of them.

Did our founding fathers consider themselves just a blip on a continuum of human spirits? Just ordinary people doing what the times called for? Like our grandparents? Like Agnes Newton Keith? Like my friend’s family members? Or did they imagine themselves something more when they wrote those famous words?

It always blows my mind: that life goes on. Our grandparents’ lives went on. The lives of everyone went on after that war. Our grandparents’ generation found their separate peace and they made new lives for themselves. They carried on, did unremarkable things- bought groceries and voted and mowed their lawns and brought their children to school- because what, really, was there to do but carry on? Carrying on is what we are built to do, after all.